How to Build a Home Dark Matter Detector

It is estimated that nearly 85% of the unknown mass of our Universe comprises about mysterious dark matter that, like some ghosts, cannot be seen or proven through physical measures. Researchers have inferred the existence of some dark matter since its effects have been seen via different astrophysical observations.

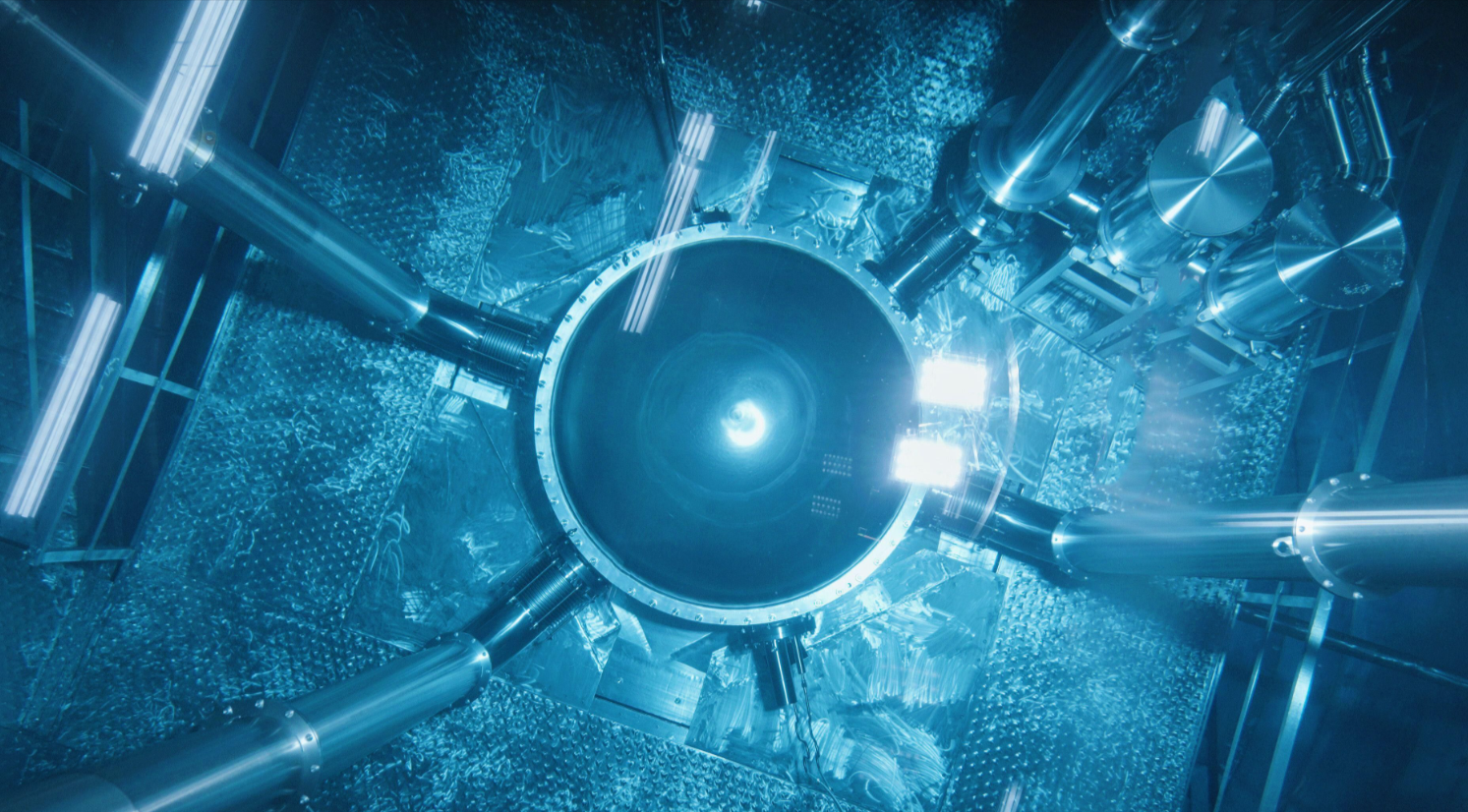

Densely packed liquid xenon fills this large tank at Sanford Lab, where physicists set an experiment with many more detectors to catch dark matter interactions with nuclei, thus emitting light. New interference cutting-edge techniques improved the sensitivity of the experiment at least by a factor of 20.

What exactly is dark matter?

According to astronomers, Dark Matter is that external matter which, they say, comprises the vast majority of the mass of galaxies, and they believe dark matter may have come into existence with the Big Bang and might have interactions only with gravity, not with other forces, like electromagnetic forces. About six times that visible matter should be purported to be contained in any cluster of galaxies in terms of dark matter, which causes them to move faster as compared to the situation that would happen if dark matter were not present.

The first attempt at dark matter was made by Fritz Zwicky, a scientist, who found that his galaxies were rotating at velocities that could not be accounted for by the light received from the galaxies. Consequently, that means that they have greater concentrations of matter than the perception that can be taken in through the light received. In truth, this search for dark matter and energy has crossed continents, from the Large Hadron Collider in Europe to NASA's Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

Physical scientists have speculated many different theories regarding the nature of dark matter. It could be everything from cold gas and massive compact halo objects (MACHOs) to strange particles that formed in the early universe such as axions and weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs).

LUX is the name of Sanford Lab's WIMP detection facility, built for finding WIMPs by their splash of emitted energy when colliding with normal matter: one short of a ton of superdense liquid xenon surrounded by sensors looking for any one of the thousands of flashes of light from a WIMP collision with its sensors, nearly a mile underground and in a 72,000-gallon tank of ultrapure water.

Its Detection Methodology for Dark Matter

While you are waltzing through two-dark matter, you will not know that they were ever near to you since they do not interact with visible matter or light. Astronomical indirect detection appears to have glimpsed these invisible particles, constituting almost 85% of the mass of the Universe, through measuring gravitational effects on stars and clusters of galaxies.

Scientists from PNNL are also collaborating in research experiments for the direct detection of dark matter such as the SuperCDMS collaboration. These types of detectors use liquid or solid state targets like silicon crystals that are sensitive to any ionization or vibration signals from the collisions between the WIMP and the target.

Another detector uses some 10 tons of liquid xenon, the density medium that set the standard for the world in direct detection of dark matter. Three times denser than water, xenon would consume almost all of the radiation reaching the center, making it possible for scientists to concentrate search locations for WIMP interactions in an area much smaller to its center, using low-pressure time projection chambers.

Dark matter has made searches from colliders like CERN's Large Hadron Collider into the light. As these machines create jets of particles, one might probably give dark matter an account of the particle physics that must be constructed to account for the hypothetical 'missing' properties of any candidate that encounters dark matter without leaving an even small trace of any residual energy or momentum.

The LUX-ZEPLIN Dark Matter Experiment is what it is called. One of the most sensitive for dark matter ever made is the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment. Located approximately one mile underground in South Dakota, this experiment is supposed to find out whether there are Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs-invisible particles that comprise most of the mass of our Universe).

For instance, the detector must be capable enough to detect rare WIMP interactions with the liquid xenon target of 7 tons. So, several thousands of ultra-clean, low-radiation components were attached about it to stop incoming external radiation and reduce internal background noise. Finally and on top of it, another liquid scintillator layer was added outside only to reject undesired signals from neutrons coming after dark matter interactions with normal matter.

Now, almost 300 days of data have been analyzed by LZ. These results, while not conclusive, narrow the options for physicists into lower energies than the onboard scientists had previously concentrated on to find WIMP signals, despite having not proved anything.

The many participants in LZ from the UK stemmed from the pioneering ZEPLIN program at STFC's Boulby Underground Laboratory which pioneered liquid xenon technology for dark matter searches that used liquid scintillators and an outer detector. Other odds and ends for LZ came from teams all over the world, including one of the two international Data Centers.

What is the BREAD Dark Matter detector?

With dark matter being one of the largest unexposed mysteries in modern physics, scientists have done all in their power to furnish it. Most of those telescopic searches have failed; hence, the University of Chicago and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have come up with an incredibly simplified and cheaper such detector, BREAD (Broadband Reflector Experiment for Axion Detection), which will very much open up darkness to the search.